April 23, 2025

By Roan Hollander

Lucy Ruxi Zuo ‘26 is a senior in Hopper College majoring in the Architecture design track. She is passionate about spaces of collective care and healing. She sees architecture as a form of resistance — one that makes visible the invisible and forgotten, and offers a shared space for truth-telling, reckoning, and healing. Roan Hollander is a Yale College senior majoring in Environmental Studies.

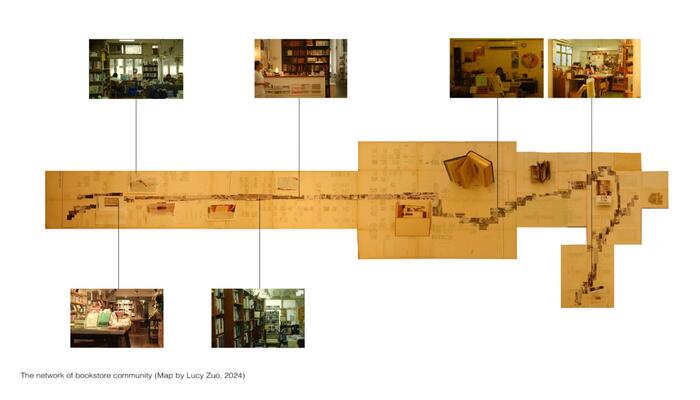

The photos included below are photos and drawings from Sarajevo and Hong Kong created as part of Lucy Zuo’s grant project.

RH: Can you provide an overview of your grant project, “Inhabiting the Cracks: Documenting Urban Vernacular Memorials”? What are urban vernacular memorials?

LZ: Interested in how space inspires healing and remembering, I have been researching “vernacular memorials” – sites spontaneously occupied, ritualized or built by citizens to express personal grief or collective remembrance. I visited Hong Kong and Sarajevo in search of different forms of vernacular memorials, from graffiti to a shared notebook in a bookstore to flowers in a war trench. I use “cracks” to describe the kinds of undefined, hidden, abandoned or marginal spaces that vernacular memorials tend to inhabit. They may be small in scale, without signage or nestled amidst inconspicuous structures; but life emerges unexpectedly here.

In Hong Kong, I encountered a community of independent bookstores that create intimate spaces for book readings, performances, workshops, and exhibitions. The dense and vertically-oriented urban environment gave rise to a typology of “second-floor bookstore” or “upstairs bookstore” - small and alternative bookstores on higher floors. To enter one of these hidden territories, one has to pass through a narrow metal gate, walk up a flight of stairs to reach a retro elevator at the end of the hallway. The floor numbers blink one after the other as the elevator trembles to a sudden stop and opens to a beige interior – just enough space for two people to squeeze in. On every surface, layers of stickers, ripped notes, and taped posters become palimpsests of people’s stories over months and years. Messages accumulate and communicate across time, becoming a living archive of the very act of collective mark-making. The bookstores invite co-authorship by allowing visitors to participate in their processes of repairing, maintaining, and renewing the space.

In Sarajevo, I joined a workshop led by Christina Chi Zhang and Kuma International (founded by Claudia Zuni) and met many inspiring artists and architects including Smirna Kulenović, Selma Catovic Hughes, and Dunja Krvavac. They shared with us how they reconcile with trauma and memory from the Bosnian War (1992-1995) through various rituals and artistic mediums. 30 years have passed, memory of the siege has taken many forms - in bodies and soil, visible and invisible. I visited sites like the Olympic bobsled track and Mostar’s sniper tower, where layers of graffiti spoke of people’s lingering pains and hopes. Next to an enormous drawing of a pair of crying eyes, a poem reads: “It is through love, trust / and knowledge / that we safeguard peace / lest such trauma occurs again.”

What was the inspiration for this project? What made you want to explore memory and memorials?

Two summers ago, I researched museums and monuments as sites of memory construction and began to question ways commemorative landscapes are defined. In Professor Yukiko Koga’s “Politics of Memory” class, I dived into “memory work” – the re-narrating and unsettling of assumed narratives of the past. I became interested in how individuals and communities find alternative ways to evoke undocumented memories by tending, reshaping, and activating space.

In Bosnia, standing in ruins of factories and war trenches that were once the frontlines during the war, I was overwhelmed imagining the lives that were lost there. But at the same time, I was witnessing the power of healing and restoration. Seeds and plants emerged from bullet holes and cracks on ruined factories, war trenches, and bombed monuments, giving new life to spaces once seized by violence and acting as a humble but powerful force of healing. They reminded me of the bookstores that grew from the narrow alleys in Hong Kong.

The community of bookstores have been striving to gather personal memories through publications, community events, and the maintenance of the physical spaces. On different evenings, a bookstore transforms into a classroom, a film screening space, a gallery, or a shelter. The bookstores are simultaneously public and personal, acting as urban living rooms where intimate exchanges between strangers can take place. They offer a different way of occupying and reclaiming space in search of hope and resilience.

How did you collaborate with local artists and collectives in Hong Kong and Sarajevo? What was the process of community engagement like?

Relationships grow out of gathering in these enduring spaces. Through repeated visits, I befriended bookstore managers, writers, artists, readers, journalists, and curators who came to these spaces. They showed me archives of zines and newspaper cut-outs of events that took place at the bookstores. We had long conversations about the process of running a bookstore, small communal actions around the city, experiences living abroad and returning home, and how we reconcile with our new diasporic identities. I shared drawings and photographs I have created and gathered of these spaces. Together, we looked at how “walls” (physical surfaces), “books” (printed objects and writings), and “bodies” (people and communities) act as repositories of memories. To document my experiences in these spaces, I made a small zine with uncut pages that need to be torn open to reveal hidden layers of images and a map that traces the paths between the bookstores on an unfolded book. I brought these objects back to the bookstores and reflected collectively on how our personal journeys relate to the stories we encounter here. These interactions inspired me to think about what it means to work in translation – not only cultural and language translation, but also the translation of vicarious memory and empathy.

What defines spatial memory practices for you? You mention in your project description that these practices are in danger – what puts them in danger?

To me, spatial memory practice refers to occupying physical space as a way of remembering. Space is not a stable backdrop where history unfolds, but rather it is constantly reshaped by its users or inhabitants. The vernacular memorials I have encountered relate to time in a precarious but dynamic way: they are often in danger of erasure, materially ephemeral or intended to change over time. They embody a kind of “living archive” that invites ongoing mark-making and reinterpretation. The bookstores possess a slowness that manifests in the everyday process of maintenance, deterioration, and accumulation. As people come and go, they bring in objects and stories and leave marks on the space. Gradually and collectively, they build an archive of graffiti, zines, posters, seeds, notes, books, stickers, performances, conversations, and memories that fill every corner and surface of the space. In the elevators, the faces of some stickers are peeled off, leaving only a white layer of glued paper. Their silhouettes, their ghosts, continue to occupy space. The stickiness represents a kind of material resistance against erasure – nothing ever fully goes away, rather they hide and linger.

What were your takeaways from your exploration of vernacular memorials?

I came to understand memory as something that cannot be preserved or fossilized in the past, but rather lived and constantly retold in the present. What truly constitutes a space for communal remembering is one that is not only about memorializing and acknowledging collective history but also about celebration, action, and hope for the future.

This research inspired me to consider the role of artists and architects in facilitating the building of communal spaces for remembrance and healing. I reflected on the processes of trust-building and translation – both their possibilities and failures – in creating spaces that invite ongoing action. We have to learn to work reciprocally by listening and giving space for the vernacular and spontaneous.

Where can people engage with your project? What is next for this project in the future?

In Fall 2024, at Ezra Stiles gallery, I collaborated with Lucía Amaya (Grace Hopper ‘25) in creating an exhibition titled “Memoria de grietas • 裂缝的记忆 • Memory of Cracks.” I’m from China and Lucía is from Colombia. We turn to each other to discover new ways of reconciling with difficult, sometimes painful memories. We believe that by understanding the other we become better equipped to articulate our own stories.

We covered the walls of the gallery with layers of poems, photographs, and sketches and surrounded the space with maps, models, and books that documented our journey visiting and researching spaces of memory. The room imitates the accumulation of messages in bookstores, ruins, cemeteries, and memorials. We both believe that “memory is a decision that carries resistance. Memory is both individual and collective. We carry it within us, but we engage in it communally. It connects us to each other and our identities. Memory is about our pasts, but also our futures. How we remember and what we remember affect the kinds of futures we imagine.”

I continue to reflect on models of resistance and resilience that can become part of our collective toolkit for place-making and remembering. I hope to not only bring the stories of the bookstores abroad, but also to carry vernacular memory practices from elsewhere back into these spaces in the form of exhibitions and conversations.

Type:

Public Humanities Grant