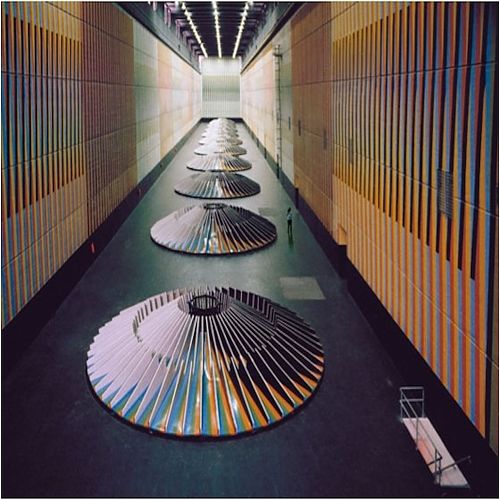

In the 1970s, as Venezuela rode the wave of one of the greatest oil booms in its history, abstract kinetic art (also called “cinetismo”) rose to the status of official visual language of the nation’s modernization projects. Reaping the benefits of the oil price hikes caused by the OPEC embargo of 1973 (a product of the October Arab-Israeli war), the social-democratic government of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-79) launched a large-scale developmentalist program known as the “Great Venezuela.” As a period of rapid urban expansion unfolded, the country became replete with eye-catching, ultra-modern murals and sculptures by Alejandro Otero, Jesús Soto, and Carlos Cruz-Diez, the holy trinity of Venezuelan cinéticos. Government initiatives such as the Museo Ambiental, launched in 1975, intensified the relation between abstract kinetic art and the era’s ambitious environment-making efforts, which led to a radical transformation of the national landscape in only a few years. In a moment that may well be regarded as the peak of this imbrication between kinetic art and oil-led modernization, Cruz-Diez and Otero were commissioned to produce two oversized works to be integrated into the Guri dam (the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant at the time), built on the Caroní River in the resource-rich region of Guayana (Figure 1).1 At its final inauguration in 1986, the dam’s massive turbine halls boasted a pair of Ambientaciones cromáticas [Chromatic Environments] made by Cruz-Diez, with a total surface area of almost three acres. As the turbines extracted electric power from the waters of the Caroní, Cruz-Diez’s colorful, vibrating murals performed a conversion of their own—that of the raw materials of metal and industrial paints into ethereal hues that appeared to come to life. Outside the dam stood Otero’s Torre Solar[Solar Tower],a 150-feet tall machine-like steel sculpture that rotated with the wind, creating a spectacle that seemed to harmonize technology and nature. In the institutional publication El arte en Guri, prominent art critic Alfredo Boulton characterized the works by Cruz-Diez and Otero as an homage to the “new Venezuela” ushered in by the Guri dam, “donde apenas hace un siglo nada había, sino leyendas, bosques, ríos y mitos” [where only a century ago there was nothing except legends, forests, rivers, and myths].2 Similar ideas about cinetismo were amply disseminated through state-financed publications like Imagen and Revista Nacional de Cultura,government-friendly popular magazines like Momento and Élite, newspapers, books,3 and even TV specials and films4 that highlighted the alliances between cinetismo and the nation’s accelerated modernization process.5 In this way, if kinetic art was shaped by the state’s environment-making and urbanization projects, it also attained the status of agent of ecological transformation by helping to remake the physiognomy of modern Venezuela.