By Roan Hollander

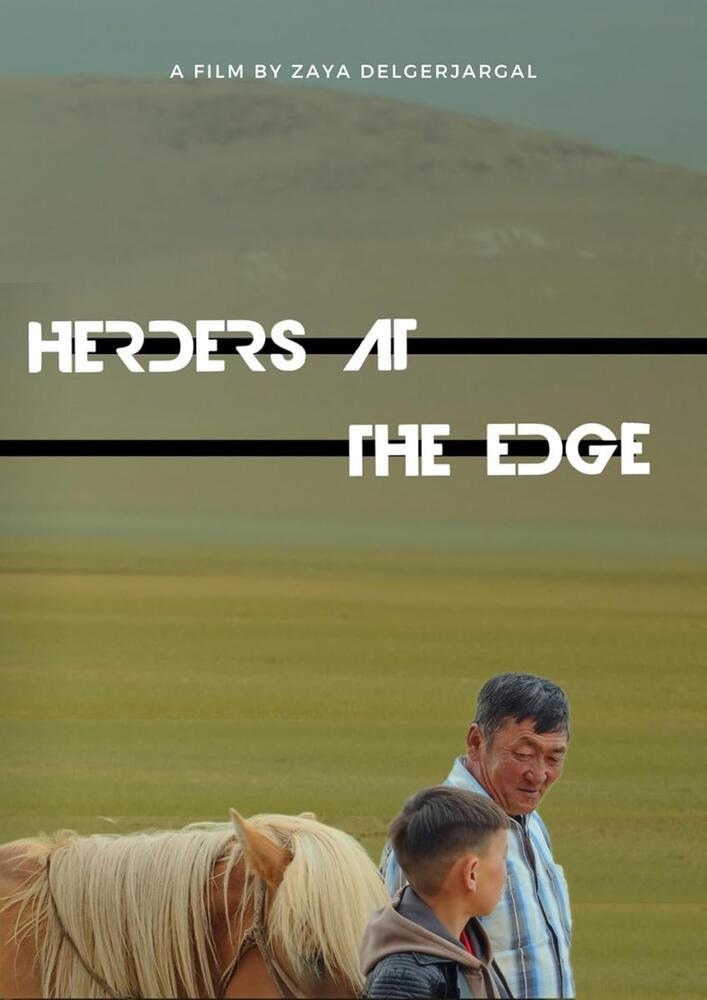

Delgerzaya Delgerjargal is a Climate Change Reporting Fellow at the Pulitzer Center, currently pursuing her master’s in environmental management at the Yale School of the Environment. She is also a producer at TenGer TV, a national news broadcaster in Mongolia where she covers local environmental issues and international events, including UN climate conferences such as COP. Her debut documentary, Herders at the Edge, has been broadcast on TenGer TV and screened at Google, Yale University, Duke Kunshan University, the Media Show, and more. The film has recently been accepted at Downstream EnvironmentalFilm Festival, Life After Oil International Film Festival, and Yale Environmental Film Festival. Zaya’s work focuses on climate change, amplifying the voices of underrepresented communities in the global climate conversation. Roan Hollander is a Yale College senior majoring in Environmental Studies.

RH: Your film follows a nomadic family in Mongolia to show how they are grappling with climate change. What inspired you to tell this story? How did you choose this specific family to profile?

ZD: When I received the YPCCC/Pulitzer Center Climate Change Reporting Fellowship, I had the opportunity to bring one climate story to life. Mongolia is home to many untold stories that rarely reach international audiences. As one of the few climate journalists from Mongolia, I felt a deep responsibility to share this story on a global platform.

I chose to film in Bayankhongor province, where my parents were born and where I spent my childhood summers. It’s also one of the regions in Mongolia most affected by climate change. From the moment I arrived in Mongolia last summer, I had less than ten weeks to complete my documentary. I traveled to Bayankhongor and spoke with several herder families, many of whom were eager to participate. Ultimately, I selected Amarsaikhan Begz, a lifelong herder with over 50 years of experience. As a state best herder, he had a deep understanding of herding life and the ways climate change is transforming it. From our first meeting, I knew he was the right person to tell this story.

How did you balance telling a deeply personal family story with conveying the broader climate crisis facing Mongolia?

I deliberately kept the focus on one family, limiting the number of people in the film to ensure each character had enough screen time. After all, the film is only 18 minutes. I then decided to include text overlays providing context on Mongolia’s broader climate crisis, reinforcing to my audience that Amarsaikhan’s family is not alone in their struggles. In the film, I chose to highlight challenges that are common among herding families, making their story a microcosm of the physical and emotional hardships faced by nomadic communities across the country.

The film highlights both resilience and vulnerability—how did you approach showing these complexities on screen?

Amarsaikhan is a resilient man who deeply loves his animals, family, and way of life. During my filming trip, I lived with his family for two weeks. This time allowed us to build trust, which was essential in capturing the raw and honest moments that appear in the film. By the end, he felt comfortable enough to share his vulnerabilities on camera and revealed the emotional toll of an increasingly uncertain future.

In your project proposal, you described current climate reports about Mongolia as falling short. What do you think is the most underreported aspect of the climate crisis in Mongolia? How does your project address this?

Mongolia is one of the last nomadic nations in the world, yet its climate crisis receives little international coverage. Most of the very few existing documentaries about climate in Mongolia have been produced by foreign media and they focus on dzud—the extreme winter disaster unique to Mongolia that kills livestock. It’s a combination of high winds, extremely low temperatures, and snow storms. While dzud has become a critical climate issue, Herders at the Edge tried to shift the focus to the summer months, which are equally important in determining winter survival rates of animals. My film explores how poor vegetation in the spring and summer delays breeding season and leads to weight loss in animals, making them more vulnerable when winter arrives.

How is climate change altering cultural traditions in Mongolia, and what does that mean for future generations?

Mongolian herding is a direct result of living in extreme weather—it’s a lifestyle that’s designed to deal with crisis and change. Herders move at least four times a year, often adjusting their migration routes within and between seasons to adapt to shifting conditions. If the region is buried in heavy snow, they move. But now climate change is pushing the already extreme climate to the next level of extreme, pushing herders to the breaking point. Some villages (soums) experience summer temperatures as low as 0°C. Herder families who once migrated to soums historically known for being free of dzud now find those areas just as harsh. This unpredictability led to many herders losing all their livestock and eventually migrating to cities, taking up jobs as truck drivers or laborers. Climate change is becoming the final push that forces younger generations away from traditional herding.

You’ve mentioned wanting Mongolians to tell their own story through oral history. How did this principle shape your filmmaking process with this family? What were there things that came through on the screen that the written word might not have been able to capture?

Raw emotions and intimate moments are difficult to fully convey in print journalism. It’s also challenging to describe places in words that most audiences have never seen. Film allows viewers to experience a different world “firsthand”—to travel across landscapes, meet people, and feel their struggles in a way that words alone cannot achieve.

In Herders at the Edge, viewers witness private conversations—between Amarsaikhan and me, between him and his wife, and with his nephew. In that sense, filmmaking is inherently intrusive, but it also reveals the most honest moments. In this way, the filmmaking process did enable Mongolians to tell their own stories through oral history. Those honest and deeply personal moments, in turn, have the power to deeply move audiences and offer perspectives they may never have considered before.

What are your hopes for the film’s impact, both in Mongolia and globally? Where can people see it?

The film has been broadcast on TenGer TV, Mongolia’s national news network, and screened at various venues in China (e.g. Duke Kunshan University), Mongolia (e.g. PMI Conference), and the U.S. (e.g. Google). It’s been recently accepted at the Life After Oil International Film Festival in Italy, Downstream Environmental Film Festival, and Yale Environmental Film Festival. We also offer private screenings for groups of 30 or more.

I originally directed Herders at the Edge for an international audience, but the film’s screenings have revealed a stark knowledge divide within Mongolia itself. It turns out that many urban residents in Mongolia have little understanding of what’s happening in the countryside. My hope is that this film helps bridge that gap. As for my international audiences, I hope that they walk away with the understanding that sometimes in certain cultures, climate change isn’t just an economic issue—it’s an issue that steals people’s dreams. One instance of this is the child jockey in my film, who really wants to be a racehorse trainer—it’s such a simple dream. Yet, whether he’ll be able to achieve it is questionable.

What advice would you give to aspiring documentary filmmakers who want to tell compelling climate stories?

I’m still at the beginning of my filmmaking journey, so I don’t feel like I’m in a position to give much advice. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that making a documentary is a huge responsibility. I hope that whoever wants to make a film approaches their topic with the honor and respect that it deserves. Also, one thing is certain in filmmaking: whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. My team and I faced countless challenges, from a car accident to a bull attack. You should plan as much as possible, but when none of what you planned goes as expected, don’t be discouraged—that’s just part of the process.