Meredith Miller and MJ Millington received support from the 2021 Environmental Humanities Grant Program for their interdisciplinary art project, Dreaming Animals, currently on view at Yale Health, which features poems by Millington and images by Miller. Miller and Millington kindly shared some thoughtful reflections on the project in a Q&A conducted over email. To learn more about the Environmental Humanities Grant Program, please visit this page. You can also read more about Dreaming Animals in a recent Yale News profile.

1. Can you tell us about how this collaborative project got started?

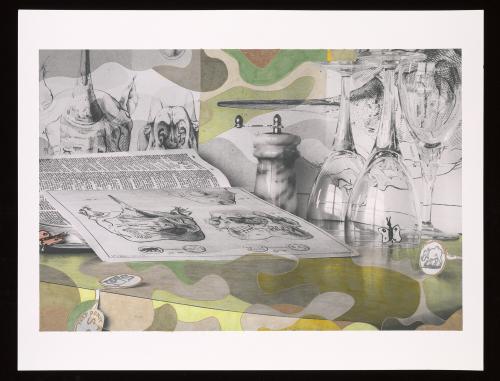

Meredith: During the COVID lockdown in 2020, I began printing out images of endangered animals from Beinecke’s digital library and creating still lifes with related household items. I approached MJ about collaborating for the Vermont Studio Center’s broadside competition. Our broadside, which combined my photograph Bird in the Hand with MJ’s poem “Worth,” was one of the winning entries, and was included in an exhibition and limited print edition in 2020.

MJ: And we had fun creating together, and conceiving the project together, so we decided to keep going, and create a whole series of photographs and poems exploring the relationship between humans and animals. It gave me personally a productive and thoughtful focus throughout the pandemic, which I really appreciated.

2. How have you used the Beinecke and Peabody collections in your project? What made you turn to historical/archival imagery, and how do these materials speak to the present day?

Meredith: The COVID lockdown presented me with uninterrupted time to be creative. To stay connected with my worklife, in which I photograph collection material, I began exploring Beinecke’s digital library. The archive presents not only scholars but also artists with possibilities to reimagine and recontextualize the past. Because I limited myself to objects within my own home, I realized, like MJ did through writing the poems, that our connection to endangered animals often exists only through ephemera and not lived experience.

MJ: For me, the historical events represented in the archival material often helped inform the story that became the poem, such as with “Zarafa, 1827,” about a giraffe that famously traveled to Paris in 1827. Meredith had included the Beinecke’s 1827 French newspaper article about the giraffe in her image, and as I researched the story of this singular giraffe, I realized that Zarafa deserved to be the subject of her own poem, as one of many famous-until-forgotten animals throughout history that have been taken from their habitats and given as gifts of empire. The Peabody material came into play in my poem “Let Sleeping Bones Lie,” which is about the fate of the rhinoceros that roamed Nebraska ten million years ago, Teleoceras major. The Peabody holds the holotype fossils of that species, and I couldn’t help but think about the ranks of drawers in dark museum basements that hold these sleeping, silent bones, and what their stories would be if those bones could speak.

3. Can you say more about the “imaginative thinking about environmental issues” that you hope to inspire with your project?

MJ: One of the realizations that we had while working on this project was the degree to which we humans use animals as symbols or shorthand about ourselves: their strengths become our exemplary characteristics (leaping like a gazelle, strong as an ox, etc.), and their perceived faults (scavengers, rats, weasels, etc.) become negative ways we characterize other people. It’s built into the ways we use language, and also the imagery we surround ourselves with. A moose is a symbol of the wilderness; therefore my collection of mugs with moose on them means I’m trying to say something about my own relationship to the wilderness. But do we ever give much thought to actual moose at all? We’ll slap a tiger on a tee shirt without ever thinking about how few tigers are left, or what we’ve let happen to them. We hope the project will spark personal reflection into something that’s all too easy never to think about at all.

4. Is there an environmental politics or ethics that this project animates for you?

Meredith: I saw the film “The Last Animals,” at the 2019 EFFY film festival which documents the devastation of elephants for ivory and the tragedy of the Northern White Rhino. Attending the EFFY film festival since its start in 2009 has introduced me to animal issues. One of my photographs is a tribute to all the sea creatures affected by climate change. I was profoundly moved by the films, “Plastic Ocean” and “Saving Luna” which partly inspired my photograph, “Harpoon.”

5. You’ve mentioned children’s games as an inspiration for the project, and indeed many of the images and poems are endearingly playful and associative. What drew you toward ideas of play in approaching the otherwise serious subject matter of biodiversity loss?

Meredith: I created a photograph for every animal featured on a piece of playground equipment at the childcare center at Wilbur Cross High School near my home – buffalo, camel, elephant, giraffe, and tiger. It’s ironic that these are the animals of American childhoods yet they’re quietly disappearing. So, the images, while playful, also speak to the more sophisticated viewer who might engage with the commercialization of animals and their use for decoration. Combined with MJ’s poems, the work takes on a haunting tone.

MJ: We didn’t want to fall into the worn-out assumption that making people feel bad about something somehow magically leads to positive change. Because who hasn’t thought about the plight of even one endangered animal and despaired, because it all seems so dire, and what can possibly be done? But doomsaying doesn’t often engage people’s hearts long-term; so perhaps promoting a different, creative approach to thinking about the problem will yield new solutions.

6. Your project combines lots of different media, including photography, poetry, and drawing. Currently it exists as a series of broadside prints on display at Yale Health, but you’ve also mentioned wanting to make a book out of it. How have you thought about format and audience, and has that changed over the course of the project? What’s next for Dreaming Animals?

MJ: We’re very excited to take the project into new iterations, beyond just creating a book from it, though we’re looking forward to that as well. I think it would be a phenomenal candidate for augmented reality, for example. I can easily imagine viewers stepping inside the layers of Meredith’s pictures, with the text right there interacting with the image and the viewer in ways not possible in 2D. Perhaps a recording of the poem would play as you stepped into the picture, which I think would make for an incredible multisensory experience. And that’s something that could be put up almost anywhere—outside, even—making the work more accessible to a wider audience, particularly young people.

In conclusion, the artists shared this poem, ”Let Sleeping Bones Lie,” to accompany the image in this article, “Rhino Hero.”

Let Sleeping Bones Lie