July 14, 2022

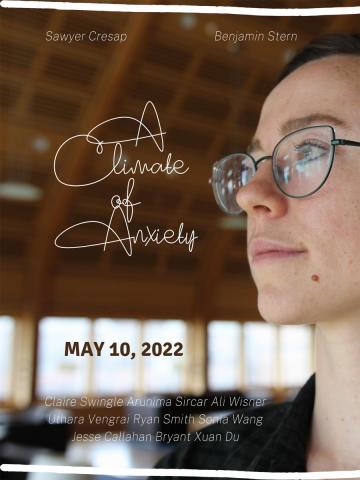

Yale School of the Environment alums Sawyer Cresap ‘22 and Ben Stern ‘22 received support from the 2022 Environmental Humanities Grant Program for their co-directed documentary film, “A Climate of Anxiety,” which investigates how climate change anxiety impacts the next generation of environmental leaders. Cresap and Stern shared reflections on the film and the role of art in climate change struggles in a Q&A conducted over Zoom with Yale Environmental Humanities’s Jake Gagne. The interview has been lightly edited for length.

JG: What led you to make this film about climate anxiety?

SC: Ben and I had been talking about film since I started a documentary filmmaking class at the Yale Center for Collaborative Arts and Media (CCAM). And I kept pressing Ben because he had so many great short films and so many interesting ideas, and one day he said, “Sawyer, I finally have an idea for a film, and it’s interviewing our peers about climate change anxiety.” Because we were master’s students at the School of the Environment, it was just the water we swam in every day. And I said, “What if I work on that with you?” And Ben graciously said yes.

BS: It’s funny that Sawyer says graciously, because I wouldn’t have been able to do it without her for sure. I wanted to work on the topic of climate anxiety, because it was pretty apparent that a ton of us are super anxious about the future and for valid reasons—and that of course people who study existential crises are going to be internalizing a lot of things. A lot of the time, people in the climate space are told to project optimism, and they don’t always feel that they have space to discuss other things. I thought it would be super interesting to talk to people and let them tell their perspective.

JG: How did you go about finding interview subjects, and what was the interview process like? Many of the interviewees shared really personal and intimate stories, so I imagine there was some trust built between you and them.

SC: The interviewees were our friends and colleagues, so we built on the social capital that we had developed over the course of a year and a half in the master’s program together, and they did us a real kindness and act of faith to to willingly share their story. We surveyed our entire cohort of graduating master’s students, just to gauge general responses to the topics, and, within that, we asked who would be willing to share a quote, who would be interested in being interviewed. From there, we did screening calls to get a sense of a variety of voices, a variety of topics, and who might tell their story the most passionate way. And by and large, all our peers are incredibly articulate and passionate, so there were so many more stories we wanted to share, but we couldn’t.

BS: The survey was helpful not just in finding volunteers to speak with us, but also in guiding our interview questions, because the survey asked, “How do you exhibit climate change anxiety, and how does it impact your relationships?”

JG: Did you have specific audiences or venues in mind as you made the film?

BS: There was more than one audience. I had described it to Sawyer before like a sort of love letter to our cohort, and so, from my perspective, they were always the primary audience, because it’s going to be a more powerful film if you know the interviewees. But,we hope that it could be accessible to broader audiences. I’m sure there’s some climate jargon, but we tried to limit that.

SC: I think you’re right, Ben, that it’s powerful to the people who know everyone in the film, but I think it’s also powerful to anyone who studies the environment on a daily basis or works in the environmental field to just speak aloud about the psychological weight that’s borne every day. But I also showed the film to my mom, and I was surprised how much it resonated with her.

JG: What future do you hope the film will have? Are there plans to screen it elsewhere or distribute it?

SC: We’d really like to see it screened at the Environmental Film Festival at Yale (EFFY) next year, and the other environmentally-focused documentary screenings. We’re not actively making its distribution public for now, in hopes that we can screen it like that in the future.

JG: You show some statistics and occasionally graphics, but it’s the stories and testimonies that are the centerpiece. I was very moved by the montage of family photos, for instance. How do you understand the role of personal narrative within environmental activism?

BS: We talk a lot about this in the field of climate communication. What changes people’s minds? What moves people? Facts and figures don’t generally change people’s opinions, especially if they disagree with a worldview. What I think influences people—or at least opens people’s minds or alters perspectives—is personal narrative, right? So when somebody is clearly exhibiting emotion and telling a personal story, that will mean more than a bar graph or chart. That’s not just in the climate space; that’s across the board. Personal stories must be central to convincing people to care more about this topic, to deal with these topics. Stories have to be central.

SC: Agreed—well said. One other point that I would add is that you [Jake] specifically called out the montage of family photos. And I think the beauty of film is that you’re not just relying on the written word; for example, you have all these other ways of conveying meeting and beauty, and I actually feel like we tried to really lean on those other means of storytelling. Like there’s particular noises we really wanted to have audible in the film. We really wanted to have human and natural beauty come forward. The original score was a big part of that too, thanks to the School of Music student we worked with, Lila Meretzky. So it’s all trying to dovetail towards making such a big topic feel personal and actually like sensible, able to be sensed.

JG: I was struck by the epigraph from Yogi Berra: “The future ain’t what it used to be.” Generational divisions are a significant theme in the film. I’m curious whether you’ve found that older generations of professionals and teachers share this climate anxiety? Is there space in academic settings to talk about these feelings?

SC: If we had more time with this project, we would have interviewed faculty more extensively. The advisor on the project is a professor at the School of the Environment, Susan G. Clark, and Susan and her colleagues have a sense of perspective that perhaps people my age and Ben’s age don’t. They’ve lived through fears of nuclear warfare, all sorts of other hard times when the future seemed really uncertain. And I only have the years that I have, so that’s a little different for me.

BS: Sawyer and I have slightly different perspectives on this. I don’t think that many professors at YSE and in the climate space in general feel anxiety like people who are millennials or Gen Z do. In a climate science class or a policy class, a professor will say, “This number of people will die because of extreme heat within the next 50 years.” And it will be an insane number of people, a terrifyingly high number, and there’s pain and suffering associated with that and with millions of people. But it’s contained within a one or two sentence observation, and then we move on immediately. As students, we’re just supposed to write it down and keep moving. I personally don’t feel like there was space to talk about the implications and the weight of what we were learning. And if the professors are feeling really anxious about it, they hide it well.

SC: And I would say every student, every professor is unique, their own person, and brings their own biases and fears and emotions. So I think that’s also something we saw reflected in the diversity of opinions in the film too.

BS: Definitely. And climate change will be worse for people in their 20s than for people who are in their 50s or 60s. Like that’s a fact, right? So that, of course, is going to create a perspective difference.

JG: Were there other films or works of art or literature that inspired your thinking as you created “A Climate of Anxiety”?

SC: Ben and I were in uncharted territory personally. We were both really early career filmmakers, and I feel like we kind of built the template as we made the film.

BS: I found it helpful to learn about environmental documentary filmmaking from The YEARS Project. I had worked as an intern with them, and I learned a lot about how they go about making films. It’s a nonprofit that made a TV show called Years of Living Dangerously, I think back in 2014, which won an Emmy. And they now work to get the word out about the climate crisis and how people can get involved. They have a really great newsletter, [Inside] The Movement, which I would love to plug.

SC: And I also should mention that Professor Charlie Musser screened a film every week as part of my documentary film class, and that certainly was a consciousness-raising for me in film just generally.

JG: Is there anything else you’d like to share about the film or about projects that either of you have coming up?

SC: It’s so important that we see more art made about things that feel too heavy to hold. Art has a place in solving the climate crisis and in coping with it as it happens, and I appreciate the Environmental Humanities program for supporting our work.

BS: I ditto that. Art has a central place in helping us deal with the emotions associated with the climate crisis. This documentary isn’t solving the climate crisis, but it is still helpful to be produced, because a piece of art has a utility outside of solving the problem that it discusses. And I don’t think that’s always laid out clearly. But the one other thing I wanted to say to your question is that there was so much we wanted to include but we didn’t. And the interviewees said so many powerful things that we didn’t include just because of time constraints and for the logical flow of the doc. But yeah, there are a few things that were said that I will certainly not be forgetting anytime soon.

SC: Ben and I have all of the quotes just ringing in our head all the time. We spent so much time with these people in the editing room.

BS: Yeah, we did. [laughs]

SC: You know how it goes.

Type:

Public Humanities Grant