December 19, 2022

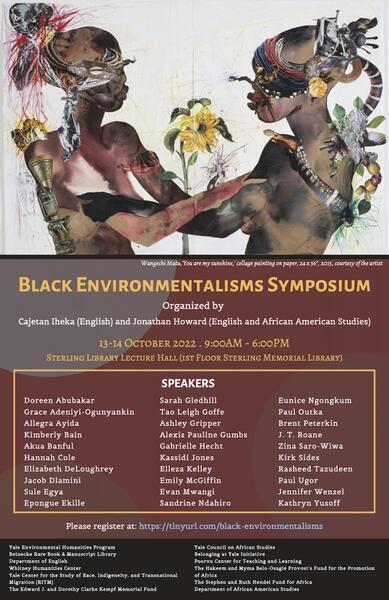

In October 2022, Professors Cajetan Iheka (English) and Jonathan Howard (English and African American Studies) convened a two-day interdisciplinary Black Environmentalisms Symposium that featured scholars, writers, artists, and practitioners grappling with Black environmental precarity across the diaspora. The symposium agenda covered diverse topics and analytical scales, including Black Planetary Imaginations, Black Geologies and Histories, and Black Environmentalisms in New Haven, and culminated in a keynote from artist Zina Saro-Wiwa.

Professor Iheka joined us for a conversation about the symposium.

Why did you and Jonathan Howard organize the Black Environmentalisms Symposium and what did you hope it would accomplish?

Thanks for initiating this discussion. We organized the symposium to showcase exciting and cutting-edge research at the intersection of the environmental humanities, Africa and its global diaspora. I initially conceived of the event as a gathering of scholars working on Africa but as I read work centered on the diaspora and as Jonathan joined us at Yale, it became clear that a bridge building conversation was overdue. I would say that the primary reason for organizing the event was to catalyze a dialogue between scholars working on Africa and those in the diaspora.

Could you elaborate on what you mean by Black Environmentalisms? What are some of the major new developments in the field?

Black people everywhere have always had a peculiar relationship to the environment. In the African context, I identified an “aesthetics of proximity” linking humans to their nonhuman environment in my first book Naturalizing Africa. This complex interaction deepens in the diaspora. Black Environmentalisms point to the multiple worldmaking projects anchored in Black cultures and epistemologies. Centering Black communities as ground zero for equitable planetary changes and insightful epistemologies, Black Environmentalisms point to the ways that the environment has been instrumentalized for oppressing Black people and to its particular significance for resistance against said oppression. The term also encompasses practices of communal care and flourishing organized around ecosystems in Black communities across the world.

The field is in an exciting state with strong work on extraction and questions of environmental racism. There is a renewed interest in environmental justice anchored in particular communities and comparative projects cutting across spaces within a country and transnationally. Scholarship in the field is also contributing significantly to the oceanic turn in the humanities, with studies thinking of Black communities’ connection to water. Jonathan [Howard]’s research offers a terrific example of this strand of scholarship. There is also the human-animal thematic that is contentious due to the historic animalization of Black folks in colonial discourse. A fascinating line of inquiry is developing at the nexus of humanity and animality, which is reorienting critical animal studies and the problematic of race.

How did you decide on the themes of each panel for the conference? Did you have previous categories that you sought presentations for, or did they emerge from submissions that you received?

We thoughtfully considered this question and decided to let the abstracts shape the organization of the panels. So yes, the panels emerged from the submissions. We were struck by the connections as we arranged the panels and even more so during the symposium.

One panel explored “Acoustic-Ocular Ecologies” while another discussed “liquid ecologies”– how are the environmental humanities reimagining “ecologies”?

The environmental humanities enables the infusion of cultural questions into ecological conventions. Within our context, for instance, ecologies are reshaped when water is constituted as an assemblage of material and supernatural deities animating Black communities. The environmental humanities allows people’s experiences of place and indigenous epistemologies to interact with–and hopefully–recalibrate our sense of ecologies. Speaking of senses, the affective dimension might be considered a key contribution of the environmental humanities to our ecological sense.

Do you have plans to host a symposium like this again in the future?

We have been humbled by the enthusiastic reception and several people have asked if the symposium will become an annual event. What I can say is that we hope to keep the conversation going. We are working on producing a volume from the event and will continue to think of sustainable ways to move the conversation forward.