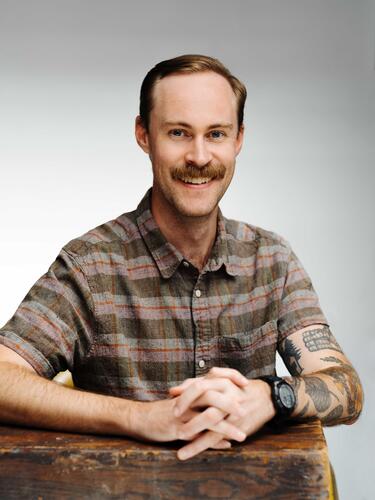

Taylor Rose is a doctoral candidate in the history department focusing on resource extraction and the military-industrial complex in the American west.

What is your research about?

My dissertation looks at the development of the US interior west, exploring the relationship between the extractive and military industries in Nevada between the 1850s and the 1990s. It thinks specifically about how Native American communities were displaced in the process of this development. In all my research, teaching, and writing, I think of US environmental history as being part of these two pillars of settler colonialism: infrastructure development and the dispossession of indigenous communities.

This project began in the Beinecke library back in 2018. I was looking at the papers of environmental feminist writer Terry Tempest Williams, who had attended peace protests in the early nineties at the Nevada Test Site. The protests brought awareness to the environmental destruction caused by the ongoing nuclear tests, but much of the protests’ culture and language were really articulated by a group of indigenous activists from the Western Shoshone nation. The activists performed a symbolic trespass onto the military lands, and when they were arrested, they presented the local sheriffs with passports signed by members of the Western Shoshone nation. I became curious about how their language of land rights dovetailed historically with peace activism and environmental activism.

Over the past few years, I have sought to research why these military reservations existed in the first place and to create a long-term history of the desert. These desert spaces were often defined as wastelands by settlers, but their resources were rerouted towards industrial mining, ranching, and other uses.

I argue that the region’s militarization continues to dispossess native peoples in a number of different ways. The Nevada Test Site still exists, and it’s been rebranded as the Nevada National Security site. There are still protests every spring, led by both indigenous and non-indigenous activists. And there are a number of military bases throughout the region that are interconnected through this long-term period of conquest.

What inspired you to pursue this topic?

I first came to Yale from Portland, Oregon after getting my Master’s at Portland State University. At the time I was really interested in the environmental history of infrastructure, particularly roads.

I had entered my Master’s program thinking about the politics of preservation, land designations, and the American philosophy of wilderness. I discovered how conservation advocates between the 1930s and 1960s legally defined wild spaces in contrast to places accessible through driving. From that initial interest in this distinction between nature and civilization, I started exploring the power relations that defined those categories. I’m trying to bring a critical, Native American history lens to how I think about that infrastructure.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law marked a historic investment in American infrastructure. What do our nation’s current infrastructure projects and challenges look like?

Infrastructure development and redevelopment have been front and center. We have all this funding to spend on infrastructure across the country, and so you see some really critical questions about where the money should go. How much should local and regional voices be brought into the conversation?

Since I’m so interested in Nevada, I’ve been thinking a lot about how the recent push for lithium mining in the state is informed historically by moments of military development. The language of “strategic and critical mineral mining” first emerged in the mobilization period right before WWII. I think it’s important that we remember where it comes from, how it frames the way we see its politics, and also how it lends itself towards excluding those voices on the ground—many of which are native people with historic claims to the land.

One of the biggest issues that the Northern Paiute communities are facing is that one of the proposed mines is actually being developed right now over the site of a documented massacre of women and children in the 1860s. It’s a sacred site.

How have the environmental humanities shaped your research?

I found a lot of commonality with people in the Environmental Humanities program in a way that conversations with colleagues in my cohort at the history department didn’t always provide. Working with students in the anthropology department, School of the Environment, or literary criticism gave me the confidence to approach historical questions that connected them better to climate change and crisis writ large.

At Yale in particular, the Environmental Humanities program really gave me a sense of home. They gave me something to look forward to every week and to have conversations in a somewhat informal manner. And it really provided me with the networks I really needed, and hadn’t found in other avenues.

You worked as a firefighter at one point. What was that experience like?

In 2012, I did an AmeriCorps program which was based in Colorado. And as part of that program. I was with a US Forest Service engine crew, which did early response to wildland fires up in the mountains as well as a number of different projects related to forest hazard mitigation. A lot of the job meant chopping down beetle-killed trees, having conversations with visitors, and putting out campfires that they hadn’t put out themselves.

Frankly, the fire conditions weren’t quite as bad as they are now. The biggest fire in the state at that time was just over a hundred 1,000 acres, and since then it’s been eclipsed by fires that are several 100,000 acres. So it’s just a wildly different experience for firefighters just in the past 10 years. If we’re going to have any sense of control or safety in these wild land spaces, we’ll need to pay more attention to the work controlling these fires.

Overall, it was a fun experience. It was exciting, and it gave me a sense of community in my small group of firefighters. That experience also turned me onto the idea that natural spaces have a history to them, and that the way these supposedly natural spaces are managed and experienced is through infrastructure. I’d say my time working there has given me fodder over the years to think about in a number of different ways.

Anything else?

I would encourage both graduate students and undergrads to get involved in the Environmental Humanities program, in whatever way seems to fit with their own kind of academic and personal interests. There’s a lot of different activities and events for graduate students in particular—there was an environmental humanities certificate implemented right as I was finishing up my coursework phase, and that’s been helpful with making my expertise more visible as I apply to jobs.

I think that the program provides a lot of interdisciplinary momentum, and without that home I don’t know where I would be able to have these ad hoc conversations with colleagues. It’s been a great forum for me.